I recently read an article about how some managers have taken to tracking remote workers’ productivity by their keyboard clicks.

If you just shuddered, I feel you.

In our Almost-But-Not-Quite Post-Pandemic age, working at least part of the time remotely is still common. However, some managers still haven’t quite figured out how to keep tabs on employees they can’t see. Fortunately for them, the Wonderful World of Software has been eager to fill that gap.

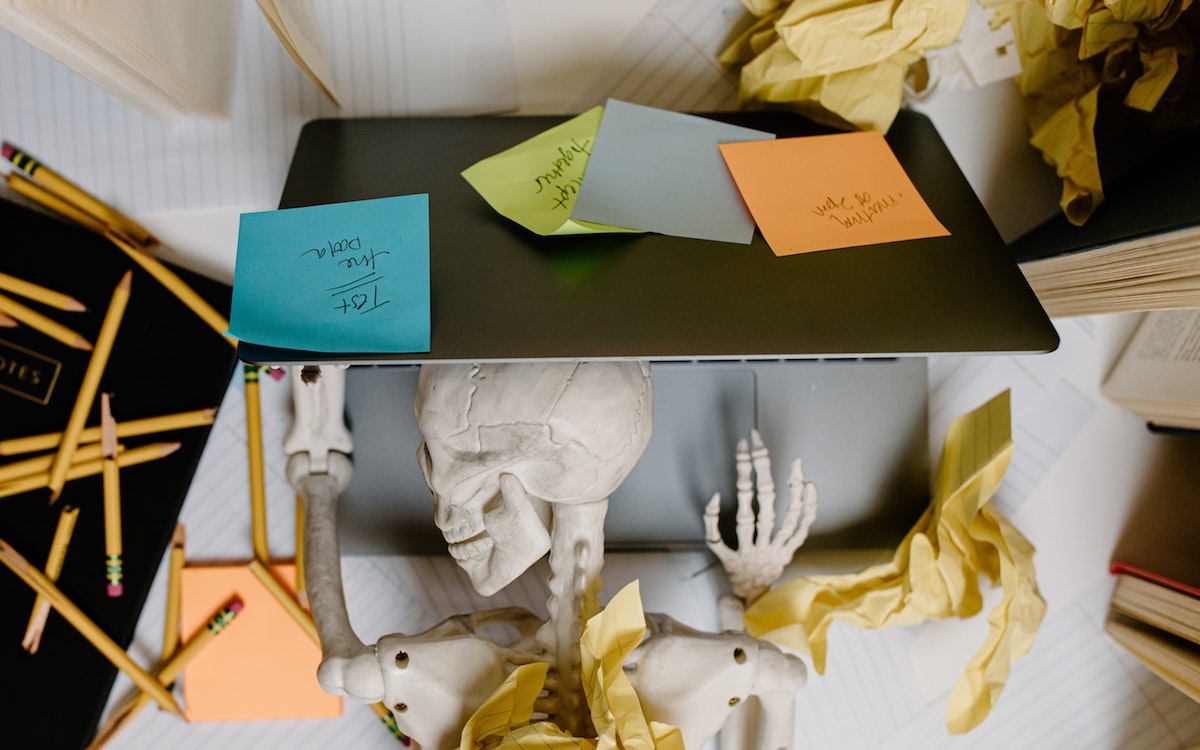

If you aren’t an employee whose every movement is being tracked, count yourself lucky. I can only imagine that working this way is the equivalent of raising your hand to use the bathroom. At the core of this dystopian nightmare is a deep level of mistrust in one’s employees.

As depressing as this lack of trust is, let’s set aside the concept of trust for this article because I’d like to focus on productivity. Particularly, I want to talk about how the very idea of “perfect productivity” is a toxic myth. The interesting thing is that toxic productivity isn’t always something that is engendered by a lousy manager.

Often, we foster the perfect productivity myth ourselves.

Why we feel compelled to be productive

Many of us were raised in a society that shuns laziness. The fable of the ant and the grasshopper teaches us that when we work hard, we are rewarded with safety and security for the long winter. When we sit around and do nothing, we suffer in the end.

laziness [ley-zee-nis] noun

1. Having or showing an unwillingness to work

Let’s not confuse laziness with low productivity. The two concepts may be intrinsically linked in our minds, but I don’t believe they sync up. In fact, most people are not lazy at all. People want to contribute. They want to do something meaningful with their lives, even if it requires effort.

Consider multipotentialites, who often have scads of irons in oodles of fires. Not only is there necessary effort, but there is also a distinct need to be productive. The drive to be involved in multiple projects or activities is inescapable. It’s hardwired into our mulitpod DNA to be productive.

That explains why we are inherently productive. But what’s wrong with being productive?

When productivity becomes toxic

Even those who haven’t endured military basic training usually imagine that it’s no day at the beach. In fact, basic training may be the epitome of a toxic work environment.

When I went through the six weeks of training in the U.S. Air Force, our unit was frequently assigned tasks that seemed pointless. One particularly frustrating job was to clean the showers, sinks, and toilets in our barracks. We would scrub until our hands were aching and blistered, every surface gleaming and thoroughly disinfected. Upon inspection, our T.I. (drill instructor) would glance briefly at the room and declare maniacally, “Not good enough.”

Back to work we went, cleaning invisible spots of dirt until our T.I. was satisfied enough with the day’s torture. At which point he would declare, “Y’all are taking too long. You can start again tomorrow.”

Fortunately, most people don’t ever suffer the indignities of military basic training. But you may catch a tiny glimpse of this type of senseless productivity in your own life.

Have you ever been forced to remain at your desk for a certain number of hours without actual tasks? Or maybe you’ve been given a vague assignment without a clearly directed outcome, so the only measure of productivity is that you are perceived to be “doing something.”

While it can definitely be bureaucratically mandated, you can also generate toxic productivity for yourself—no bad management required. For example, many freelancers can feel the need to put in a 60-hour week even when the amount of work doesn’t warrant that level of performance. For multipotentialites, the risk of this type of overachieving can be high. It starts with genuine excitement about doing something new, but can quickly descend into pernicious productivity when there aren’t clear boundaries for finishing.

When you combine unclear directives with a culturally-infused sense of diligence, you get low enthusiasm, depression, and burnout.

So how can we tell if we are being productive on any given day or at any hour? Unfortunately, there isn’t a scale that can measure true, positive productivity.

That’s because the definition of productivity is fluid. Which is why it’s never actually perfect.

Redefining productivity

If you think about it, the definition of productivity changes depending on the person and the activity. Measuring true productivity is all about circumstance.

In our earlier Orwellian example, we found a manager attempting to track their employees’ level of productiveness via keyboard clicks. But let’s reflect on this for a minute. How wrong is that, really? Suppose that an employee is hired to output strings of characters, no matter if they are meaningless gibberish or accidentally coherent. The task at hand is literally keystrokes. In this case — although it sounds like a mindless job that would drive most of us to distraction in five minutes — it’s in the job description, and one could expect to have their clicks tracked.

By contrast, if the job description is writing articles to inspire other humans, then there will be a lot of gaps between clicks—hour-long gaps, or even days. I speak from experience. Here, tracking keystrokes performed during a given period is not an accurate measurement of productivity. Turning in an article on time is more accurate, and more than likely appreciated.

But that’s all about a manager or an editor defining our level of productivity for us. What about when there’s no one around to track us at all? Does our productivity make a sound? In other words, how do we measure it?

Sometimes, there’s an easy metric. Let’s say that you have an art show coming up and you must complete ten paintings before the big day. Right now, you have… none. You have a certain amount of time to get ten paintings done. You also know that you have your full-time job and kids to take care of. There’s your metric. You define your level of productiveness by the number of paintings you need to complete daily. Maybe on busy workdays, that will be zero, and on weekend days where someone else handles the kiddos, it’s one.

What if there isn’t an easily chartable metric? I think about this with my running. I enjoy running for running’s sake (don’t hate me) but there’s no tangible output. Yes, I want to make sure that I make time for it. It’s important to me that I run and that I get better at it. But how can I tell if I had a productive running day? I could set myself a certain number of miles or minutes to achieve. But, unless I’m training for a marathon, those numbers are not really that important to me. So sometimes, a “productive running day” simply means that I put my shoes on and go around the block. Sometimes it’s even just a walk. I did it! That’s it.

A similar example is working on a choreographed dance. There are no widgets to point to or reports that provide easy metrics. So it could be that your level of productivity is measured by time, like, “rehearse for two hours.”

Especially for multipods, who might work on many varied things in a day, it’s essential to know what will make you feel productive in each area. You have a much better chance of feeling productive if you define what that means before you start. Then you know exactly when you can kick back and celebrate a job well-done.

Productivity is not life!

No one achieves perfect productivity. Even if you reach a useful metric set by yourself or someone else, there’s more to life—and work—than charts and graphs. What if you weren’t productive at all one day? That doesn’t define you as a person. In fact, it’s important to have unproductive time in your life.

Perfect productivity is a myth. And we don’t always get gold stars or paychecks, even when we achieve what some might consider super high levels of being productive. Being productive for productivity’s sake is a form of abuse, whether it’s done to us or we do it to ourselves. When you leave your office or studio and lay your head down at night, the only thing that really matters is that you existed. If you managed to do something good in your day, even if it was simply being a friendly face to someone else, you did good. Even if there was no software to track it.

Your turn

In what ways have you experienced toxic productivity, either from someone else or self-induced? Share your story in the comments!

At a place I used to work, I was carrying about 10 weeks of available PTO I didn’t have the time to use because we were often short-staffed. This included several days per year of available sick time. If you took scheduled time off (for example scheduled vacation days), this day was not counted in your daily, weekly, or monthly productivity numbers. However, if you called off sick, even though you had the available sick time available, because it wasn’t scheduled sick time, the day off would count in your PTO. You were expected to work 90 to 120 accounts per day. So, for that sick day, you would not work any accounts. Therefore, instead of 90 to 120 accounts worked, you would have zero. You can imagine how this would destroy your ability to meet your required productivity numbers for the week. Your productivity affected a lot of things like annual raises.

Hi Michelle,

Wow, that sounds like a very impersonal work environment, to say the least. I hope you moved on to something better!

Tracking keyboard clicks?? Oh dear. Surely a better measure of a worker’s productivity is to simply ask the question ‘has the work been done?’. How, when and from where the work is done is largely irrelevant. And I do agree with you D.J., it’s not always about being able to measure productivity. Downtime can be very purposeful and therefore productive in ways that are difficult to define.

Yes! I’m happy to see that a lot of smaller tech companies I’m familiar with are not only okay with downtime, but encourage it as part of being a healthy and productive employee. It’s gratifying to know that things are changing in some places.

From a young age I grew up being pushed to be working constantly and if I was idle there were unpleasant consequences. Unfortunately, even now as an adult I feel that if I’m not bone-tired and brain-weary at the end of a day something ‘bad’ may happen to me because I just didn’t work hard enough. Some times I just rebel and take a mental health day and do ‘nothing.’ There’s a happy medium in there somewhere, I just haven’t found it yet…

Hi D,

I think you’re not alone in using a mental health day to get some rest from the treadmill. That’s a symptom of toxic productivity if I ever heard one.

Many people grew up in similar environments (I certainly did), and it can be hard to let go of those feelings of “guilt” for not being exhausted at the end of every day.

Sometimes when I get caught up in those feelings (still happens), I have to consciously stop, breathe, and look back through my day. Most of the time, I realize how much I actually accomplished without having been aware of it in the moment.

Other times, if I look back and see that I didn’t hit all my goals for the day, I have to practice forgiveness of myself. I’m only human. Then I work out whether or not I need to “make it up” the next day, or adjust my future goals to be more reasonable.

It’s a process!

Mental health days are good. I’m an advocate. 🙂