Ah, learning. A multipotentialite’s delight! We love learning for its own sake and because we can always find many ways to apply any new skill or knowledge we take on. Rapid learning is a multipotentialite super power, too. Sometimes we feel like infallible knowledge acquisition machines. Until we don’t.

Take learning to play guitar

At first we rapidly improve—one week we’re completely useless and the next we’re strumming a few songs. After that our improvement continues, but more slowly. Perhaps we’re learning some more difficult chords and a few scales. After a while, we become an okay guitarist.

But “okay” is where many of us hit a ceiling. From this point, to truly master this new skill, we have to put in a ton of effort just to make a minor improvement. Becoming a master guitar player requires endless practice of the tiniest details. Improving starts to require several times more than the total effort we’ve put in so far already.

If we naively expect our rapid early gains to continue, then this is often when we get bored or demoralized, as it sinks in just how much work it is to improve further.

I think we can apply a remixed version of the Pareto Principle here. Maybe you’ve heard of it? As principles go, it’s one of my favorites – partly because it’s fun to say, and party because it’s super useful and shows up all over the place.

It’s also known as the 80/20 rule: for many events, about 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes.

For example, large corporations have noticed that 80% of their complaints come from 20% of their customers, so solving their specific problems reduces overall complaints by a tremendous amount. In software, 80% of bug reports comes from 20% of bugs – fix those, and you’ll stop drowning in quite so many reports.

The principle isn’t just about negative effects, either. Tim Ferriss, author of The 4 -Hour Work Week, claims that 80% of your productive work is achieved in just 20% of your time. He uses this insight to argue that you can focus on the super-useful 20% of tasks that bring you 80% of your output.

Here’s my 80/20 for mutipotentialites: Mastering a skill up to 80% ability takes about 20% of the effort.

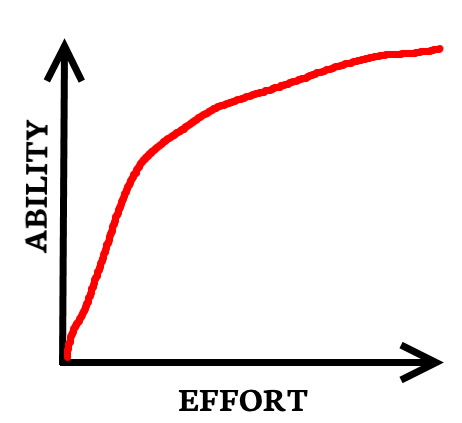

Our biggest gains in proficiency come when we begin something new. I’ve drawn a Not-Very-Scientific-At-All Graph to illustrate the point:

That initial 20% of effort can take us a long way. Think back to our guitar-playing example. It takes discipline to climb the far end of the graph!

When we hit the ceiling of being “okay” at something, we have a choice to make: Is this good enough? Or do I want to put in all that effort again and again for ever-smaller improvements?

There’s no right answer, of course. It depends on what you want to achieve.

Multipotentialites often value breadth over mastery in many areas of their lives, so this principle can help to plan in advance: When I hit that point of being ‘good enough’, I’ll move on to something new.

Knowledge of the 80/20 principle of learning means you can make a conscious choice, either to stay disciplined and keep improving, or to move on and throw yourself into the next exciting thing.

Whatever you choose, don’t feel guilty

We’ve talked before about not feeling guilty about failure to finish. There’s absolutely no rule anywhere that states you have to master whatever you start. And of course we can master some skills and remain merely ‘okay’ in others.

It’s totally acceptable to learn a bit of this and a bit of that

And chances are that you can apply what you’ve already learned to whatever you take on next.

It’s all about what we want to spend our effort on. By knowing how learning works, you can recognize the point where effort will no longer bring you much improvement. Then you can decide what to do (or not do) next.

Your Turn

Do you move on when you get ‘good enough’ at something, or do you like to fully master it first? Or both? Share your story in the comments!

Thanks, Neil. That was a very educational post!

As for my own learning: I think I’m one of the “both” people, although I do think I tend towards the “good enough” side of the spectrum for most matters. Depends on the topic. I amazed myself at how quickly I learned to play my first violin last year. Hey, when I just got it, I was playing several hours a day. But nowadays, it seems to get harder instead of easier. (Although I admit that a severe lack of practice together with new interests since I got my present job will be part of that… 😉

In my writing however, I’m much more of a perfectionist. Or that photobook/storybook that I’ve been working on since last August, and which is *still* not quite of the perfection I envision it.

Personally, the problem I often experience is that I master something to a pretty good level (probably your 80% or so) on my own, and then, when I go looking for a course or something to further improve my skills because I seem to have hit the ceiling at what I can learn on my own, it’s difficult to find something that continues where I have left off. I may have skipped over some basic skills in the area, yet have fully mastered a far more advanced skill (which was what I originally wanted to learn). Take playing the organ for example. I’ve never had lessons, and I have but a very basic grasp of the chords and what goes with what. But I can play multiple pieces in three or four voices (like in a choir).

Another example is rostering (making timetables for schools etc). There’s courses for that, but they start at the very beginning. And simply learning by trial and error, I’ve progressed waaaay past that level… But try and explain that to a possible employer, who wants to see that I actually learnt it *right*…

Sigh… Someone feel like starting an online school or so with courses specifically for people who’ve already mastered so much on their own?

This very thing happens to me all of the time. I too excel pretty quickly when I am learning something new but loose interest when I get to a decent level of proficiency. I have always longed to be an “expert” in something but have been frustrated at the amount of time and effort it takes to get that extra 20%. Now I know I am not the only one who feels this way. I like that you phrased this as a “choice” you can make and if you choose to move on that it is not a bad thing. It is tough though in today’s world where people are always looking for what “creds” you have and who you learned what from and if it was legitimate or what have you. I know what I know but it is hard to convince others of that when you need to in a job situation or even in conversation with other people. Another timely post Neil! Thanks!

Bingo!

I have been told that it’s the “idea” of a particular thing that I like rather than the “thing” itself because had I liked the thing, I would have mastered it already but there are just so many things in the world. Same thing bores me up or I don’t see enough RoI or maybe I am too lazy to delve into the details

My day jobs is in continuous improvement, which is where I first heard of Pareto’s Principle. However, I’ve never applied it to my hobbies. I like the idea of giving myself permission to learn a skill without the obligation to master it!

Fantastic! It’s funny how difficult it can be to give ourselves freedom like that 🙂

Wow, you hit on one of my hardest challenges. I’m the type that moves on. I never completely abandon an occupation, I still work as a veterinarian part time, but no longer bother to take cont. ed. seminars. I still do photography and photoshop, but only occasionally watch a u-tube video on the subject, no more full day seminars or cont. ed full semester courses. I’m in documentary film making now, learning the different skills involved from camera operation to lighting to editing. I’m into writing now… It’s lots of fun learning new skills. the problem is that I never get to the point that I’m as good as someone who does only that and obvious that’s who I compare myself to…

Comparison is tough. My rule is to (try to) only compare myself in a way which serves me. If it helps me to be better, great. If not, no point in comparing! 🙂

Excellent post! The same concept can be applied to another perennial problem–weight loss.

Many people start strong with rapid losses, but as they progress, the losses are slower and require more effort. That is when most people quit.

I think the key to mastering anything is twofold: 1) never quit, but 2) always learn/act in different ways. In learning to play a guitar, maybe at the point of being “okay” you change from an acoustic to an electric, or from a 6-string to a 12-string. Make a change to keep it new and exciting.

In weight loss, when you feel as if nothing is happening, find a new activity to burn calories, or maybe even just find a new cookbook for different recipes. Anything to keep things fresh.

Great post!

Interesting! Novelty definitely keeps me going. And yes, once you decide to master something it’s a great way to stick with it – of course, we always have the option NOT to master something if we don’t want to. Thanks for sharing, I love when comments like this add to the posts!

Very nice written and informative.

It often happens to me. I am attracted to new things and I leave the present task. So now I keep on doing the task until I master it. I keep on practicing that task and giving all my efforts to it.

The way I know I have mastered the skill is when it comes in flow. Once I have mastered the skill I am able to do that task effortlessly and in flow. At that point of time I realize that it is time to do something new.

That’s great, Parth 🙂 Identifying a point where YOU are happy to stop is what it’s all about. I love the flow-feeling that comes from sufficiently mastering something 🙂

Thanks!

I came accross this situation multiple times already. Learning a new programming language? No problem. Mastering every design concept behind it? The return on time invested is not interesting (and stackoverflow does exist for something).

I taught myself photography, and a lot of people tell me that I have really beautiful pictures, and a good eye. I always respond “yeah, but I still could do this and this and this”. But the effort to go there is immense. Maybe one day I’ll do it, but not now.

It’s true, putting 80% effort to learn the 20% skills/knowledge remaining/missing is quite often demoralizing, especially when you try to compare actual progress to “before”.

Exactly! I view programming as a tool, and I strive to get better, but I don’t need to understand every instruction being loaded into the CPU to make my programs work well 🙂 Two great examples!

Oh yes, this is me! I love learning new things but only up to a point. So many interesting things to learn, so little time. The advantage is that I can turn my hand to lots of different things, the disadvantage is that I rarely feel the expert. And the world seems only to value experts, or at least it did until recently. I’ve definitely become more comfortable with this over time, but this is the first time I’ve seen it framed as a choice and that’s really refreshing.

Thanks Helen! Breadth is just depth looked at sideways, so all your knowledge from different domains added together makes you an expert in the combined field 😀

I love that viewing it as a choice feels refreshing. That’s the point of the post, to help remind us all (and I need this reminder often too!) that we have the freedom to choose exactly this, and we don’t need to pressure ourselves unnecessarily if we don’t want to.

Well I just want to master everything that fascinates me(that too 100%). But the problem is that I am fascinated by almost everything. And hence am facing a hard time accepting the fact that I can’t do everything(that I love) perfectly. But right know I’m not even eighteen, so I guess I’ve plenty of time to master everything.

I hope ??I can be happy if I just learn the right thing at the right time!!

Thanks’ for this article.

Learning the right thing at the right time is a great attitude to have, I think. It takes time to accept that we can’t be perfect at everything, but there’s a lot of freedom that comes with that realisation.

Great piece Neil.

You know your audience. Much like the other respondents here I am very similar in achieving the 80% when learning a new skill and tailing off thereafter. However I would argue the feeling of remorse we used to feel before you helped us understand we don’t have to feel guilty, came about by some myth that we have to master something! Even people who have mastered skills still never feel they have and will be critical of their work or performance. It’s also my belief that we can never ever master anything there will always be room for improvement and that’s the problem.In this era of technology at least we are aware that nothing is ever complete now, everything is in Beta, there are always new updates. Everything is vibrating, always, so nothing is ever still, solid or complete so nothing will ever be perfect or mastered or if we think it is it will only be fleeting.

As multipods, I think once the learning becomes repetitive for us that is when the fun stops and the interest.

Love the not very scientific graph by the way 🙂

Duncan

Exactly! We buy into a lot of myths – often they’re useful, but sometimes they don’t serve us, and it’s always worth learning to tell when that’s happening so we can let go.

Haha, glad you enjoyed the graph. I spent many years studying the ancient art of graph making to achieve 80% mastery of it, and this is the result 😉

“At first we rapidly improve—one week we’re completely useless and the next we’re strumming a few songs. ”

That’s kinda never the case. The 80/20 rule was never meant to be applied to skill building, it’s simply another way to express ‘normal distribution’ … that 80% of your sales will come from 20% of your clients, etc … in other words a situation where there is a large pool of choices.

Strumming a few songs in a few weeks isn’t 80%, or even 8%. It might take five years to get that first 80% and 25 years for the other 20%.

I REGULARLY see this with my students, web design for example. They are so so so confused for 4-6 weeks and then a critical mass is reached and it starts to mesh for them.

It’s like building a puzzle … you can’t see the bigger picture until you get a critical mass of pieces in place.

It’s not Pareto.

Thanks for this, Randy! I totally agree 🙂

In the original draft of this piece I went on a huge diversion about how you can’t really measure “effort” or “skill” very precisely, so not to get hung up on the numbers… the point was the continual re-evaluation: “is the amount of work required going to lead to worthwhile results for me”, along with the realisation that the balance of this equation is constantly in flux.

This is also why I emphasised the unscientific-ness of the graph – there are so many variations to skill-learning. It all depends on the timescale you view it at (perhaps your students will look back in a few years time, and those 4-6 weeks of uncertainty seem like nothing, and they did get to a high level of competence relatively fast… but there’s still so much to learn!). And on individual aptitude. And whether or not you’ve learned, say, a different musical instrument before.

So I wasn’t trying to sum up all skill-learning in one paradigm in a few hundred words. I think all a blog post can ever do is to provide a jumping off point for self-evaluation, and hopefully this analogy – flawed as it is – will help a few people to choose how to allocate their time 🙂

What a concept! I’ve also always been this way- learning new things only so far as I needed to, and quit before it became truly difficult (HTML and Spanish being two examples). I’ve always been aware of it, but never in such a precise and self-aware manner.

This pretty much sums up my whole life- everything I’ve ever done- from writing, playing clarinet, crochet, blogging… That said, I really, truly do want to hone a craft- to truly excel at something. I’m trying very hard to learn my latest craft, latest obsession- polymer clay- and I’m still in the happy learning phase. Only the future will know how it plays out, but I want this to be the one that sticks.

Talk about hitting the nail on the head. I am all of the above and have beat myself up over it for years wishing that one day I would be become an expert at something. Going back and trying to learn a new way may put new life on an old subject but I think my brain would somehow still be looking for a new subject!

Oh to be a singlepotentialite!

This rapid learning has put me in awkward places throughout my entire life. Whenever? I join a class? for beginners?, I end up learning too fast and it’s especially awkward in dancing classes where most can’t partner with me. Nevertheless, I would still need much practice before joining advanced classes.

I think it is possible to master an skill in months. So it is possible to be a master on moving to new areas and to master them.

Love Love the graph, a perfect example of good enough. I only proceed past the 80% if it is something I need to do or things my brain will not let go of, Must perfect my skill! Some things continue because they bring me pleasure in the doing.

Ditto on the awesome graph, especially the footnote.

Thanks Neil. I always appreciate your posts. I tend to beat myself up over being the “jack of all trades, master of none” and it helps to have a different perspective in lowering that level of self-imposed guilt.

Thank you for this article. I feel tremendous amounts of guilt, as I still have not mastered the piano. Each time it gets harder, I want to perfect it and spend an enormous amount of time. But as I get busier and I don’t have time to practice, I feel as if all of that time I invested has been wasted. So, then I go to my Art Studio and begin on a painting. The paintings always get done, whether they take a day, a week, or a month to complete. But with music, unless you can practice daily, you fall back to the beginning. And that get’s frustrating.

If you haven’t watched this Tedx – The hidden power of not (always) fitting in. by Marianne Cantwell then her talk should resonate well with this topic. She uses a simlar term to “not feeling good enough” as being “liminal” which has the same definition of not staying with that “one thing” after getting to that certain point. I like her analogy of being on a secluded island. Some people will decide to stay on that island and others will want to leave and explore other “islands”. I myself always got back on the boat and went on another journey. Nevertheless, I’ve always been hard on myself for not staying on that island. But like Neil said we can’t be too hard on ourselves. Besides, look at all of the possibilities that lies outside our tiny little islands! There’s so much more to explore!

I find that I quickly dump a new interest when I haven’t nailed down some goals right from the outset. If I haven’t created a necessity to learn the skills and made commitments relating to them, I’ll soon lose interest in learning. I recently tried coding, I signed up for courses, started doing tutorials – then gave up on it within days. The reason – I had absolutely no idea what practical use I would have for those skills and no benchmarks for measuring my progress, so the motivation to stick with it just wasn’t there. I walked away with no hard feelings.

On the flip-side, I took an interest in electronics for several weeks because I had a broken TV I wanted to fix – I joined lots of forums, got plenty of helpful advice from experts, I learned what all the components were, bought the test equipment I needed and learned how to use it, how to safely discharge stored charges, how to replace failed components etc… and, I got the TV working again! The goal I set had been achieved, and I happily put that interest back on the shelf for another time. Had I acquired another failed device during that period, I probably would have set myself another goal to reach for.

So – if I’ve not managed to find a satisfying reason to reach for the next milestone of achievement in a subject, it’s time for me to move on.

I’m playing the violin for 1 year now, and the rapid learning phase was incredible. In fact, according to my teacher I play better than some others (mostly kids) who are playing for 3 years already. I was afraid I wouldn’t stick with it, but it gives me so much joy and I want to learn this until I can play beautifully, so I intend to play the violin for all my life, because it takes a lifetime to master this, haha.