If One Uses Soft Words, Even Plain Rice Tastes Good is an introspective photobook conceived by Kashmiri Australian designer Priyanka Kaul and manifested as an ode to her parents’ parents’ homeland, Kashmir, located in India: a region to which she is denied access due to longstanding civil unrest. A native soil she’s tilled, via a fertile imagination, 7,000 miles away on the island of Japan.

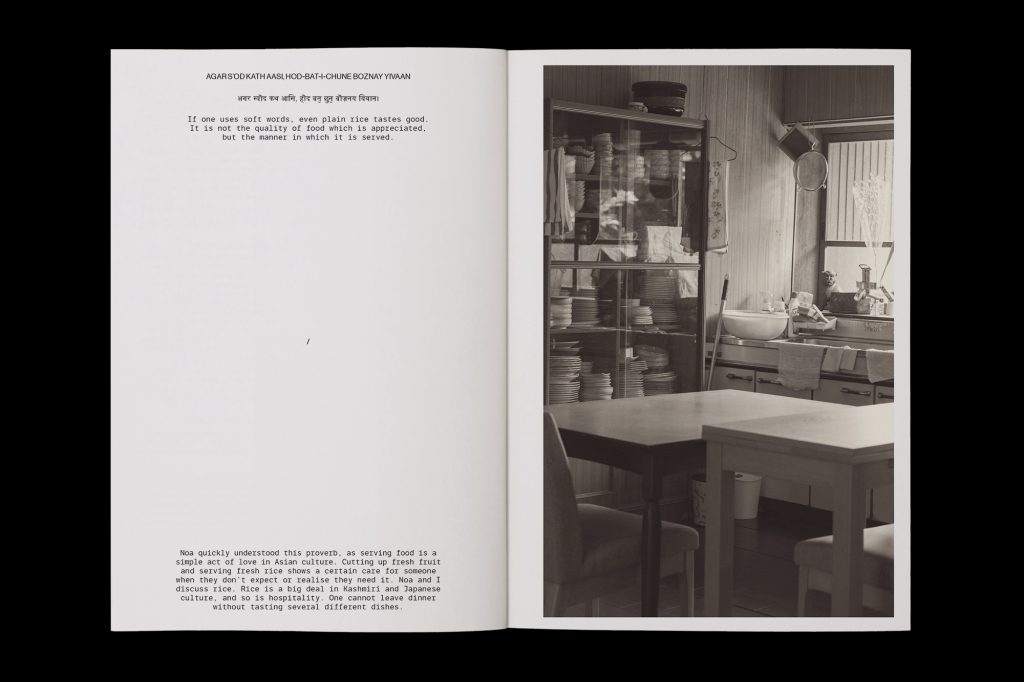

If One Uses Softs Words, Even Plain Rice Tastes Good marries old and new. Time-tested Kashmiri proverbs come to life through a ballad of contemporary photographs shot in collaboration with Noa Nguyen, a Vietnamese expat who’s made Japan her home.

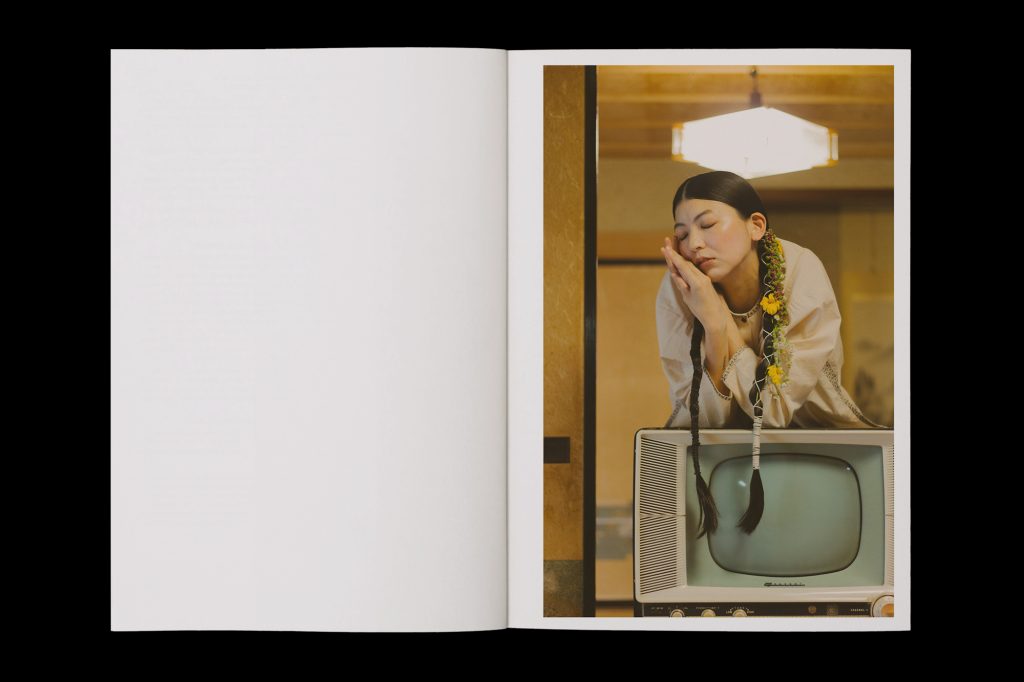

Inside the photobook, models Hako and Nao take on the role of fictional friends who embody the wisdom of Kashmir through their double gaze and subtle gestures. Other images hint at earth offerings: food, flowers, water, wood, stone. And then there are those pensive portraits of the project’s main locale, a restored minka home, set apart, along one of the island’s idyllic landscapes.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Malika Ali Harding: How did your family arrive in Australia?

Priyanka Kaul: My parents tell me the main reason they came to a new country was, apparently, my horoscope. My birth chart said I would do great things, but overseas. The Hindu priest who performed the reading asked, “What is she doing here? She shouldn’t be in this country. She should be elsewhere. She’s meant to do great things elsewhere. And so my parents were like, “Oh gosh, okay! We’ll go somewhere else because our daughter’s prosperity is linked to it. And of course, my parents were newly married also, so they wanted to get a fresh start somewhere else.

Wait, what? Are you the only child?

I have a younger brother. There’s a six-year difference between us. He was born in Australia. We’re very different. I’m more the keeper of our culture. He doesn’t have as many memories of India as I do, because he didn’t get to go back as often. And neither of us have ever been to Kashmir, where my family’s from. My mother is quite scared of us attempting to go. She doesn’t want anything bad to happen to us, especially since it’s still war-stricken.

My family comes from the first inhabitants of Kashmir. They’re known as Kashmiri Pandits. They are the indigenous people of Kashmir and inhabited the land 5,000, or more, years ago.

In the 1980s to early ’90s, there was a mass exodus of Kashmiri Pandits. Many no longer live there. They migrated all over the world.

What prompted the mass migration?

Multiple things. It was politics. It was religion. It mainly started, they say, from the India-Pakistan split. There’s always been fighting over Kashmir and who owns it. Kashmir has been ruled by many: Afghan rulers, Moghul rulers, Sikhs, Hindus, Buddhists. So many different religious rulers. Some have been good for Pandit; some, not so good. With each century, there would be a change—destruction of literature and conversions. [At the end of this last century] Kashmiri Pandits were terrorized and told to leave Kashmir or face consequences

They’re at home in Kashmir, but they live as refugees?

They’re still there in camps and tents waiting to be given back their land, titles, and everything else. My family was lucky that they left before the major events of the exodus, but my grandfather and relatives from that generation and beyond don’t talk about what happened.

I think people just don’t want to recreate that pain. There are a lot of proverbs from Kashmir about forgetting and moving on.

That’s one of the motivators for me making this book. I’m hoping to protect that history a little bit. To conserve it so that my children know and don’t feel that gap and void.

Everything is destiny.

Kashmiri proverb

Are you at home in Australia?

To be honest, I’m in-between these two different cultures [Kashmiri and Australian]. One, which is very much about superstition and horoscopes and belief in destiny—a strong belief in destiny. And then another culture, which is very much, like, you can build your destiny. You can change it, you know? And I’m always shifting between those two.

This push and pull shows up in my favorite section of your book.

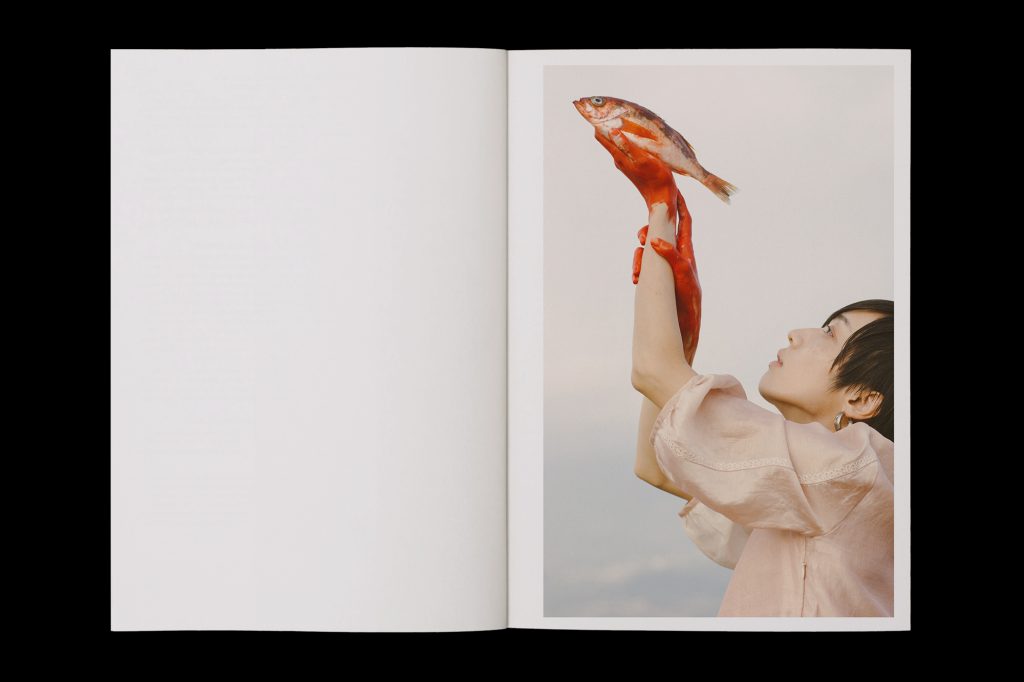

I mean, the whole entire book is beautiful, but the section about destiny really spoke to me. You have the model standing in the sea holding a fish with red hands.

Your photographer, Noa, explains that the fish represents human decision; and red hands, a higher power. So it’s a symbol of this dance between our will and the will of the gods, gorgeously illustrated in this set of photographs. I really sat with that section of the book for a while.

I’m so glad. It’s interesting, everyone has a different sort of emotional reaction to the book and its imagery. Some people get quite nostalgic and think about their own culture and their own connections, which is exactly what I wanted. I knew this book would be purchased by people that were interested in documentation of their cultures. It’s just amazing when people say, “Oh, I remember back home in Russia, we used to talk about these kinds of proverbs and we used to eat this kind of food. And this book just brought me back to those memories. I’m going to document something about my culture now.” I just think that’s really beautiful that I could, you know, manifest that in people. It just feels really good.

Listening to you, I now realize why I was so attracted to your book. I’m in the process of documenting family history and lore. I really want the generations that come after me to know our past.

Let’s take a step backward. You’re a designer of handwoven silk garments. How did you arrive at creating a photobook?

It’s a sad story, actually. My most recent collection got stuck in customs in India last year due to COVID-19, so I still don’t have it. Because I lost that investment, I tried to take a positive spin on it and try to make something outside of fashion for a while. Documentation of my culture is something I’ve been wanting to do for ages. I wanted to combine all of my artistic skills into one book. Instead of working with a photographer, originally I was going to make paintings of each proverb.

Then I decided that I really wanted to link my fashion background and label to the book project. I thought about how I could merge all of my worlds together. When I came across Noa and her work as a photographer, I began to reimagine. Noa works in Japan. And Japan is the closest I’ve come to Kashmir, if that makes sense.

Kashmir was a central point for the silk road at one point. That meeting point of Western and Eastern culture. To me, that’s what Japan is. Like when I walk down the street in Japan, I see the skyscrapers along the road and then, suddenly, it turns into this beautiful walkway with shrines in the middle of the city. You know, it’s just that balance between the two different cultures in one space.

That’s my hope for Kashmir. That it would one day become that, because it was in the past. That buzzing atmosphere. That connection between regional and suburban and urban. Japan is just so seamless and beautiful, and yeah, it just reminded me of what Kashmir could have been and what it was, when I wasn’t there to see it. If there wasn’t terrorism or unrest, in my eyes, Kashmir would have ended up being a lot like Japan.

I dreamt of hands plunging into the depths of the Dal Lake, drawing out lotus stems and stacking them like little white sticks on boats. This was Kashmir, the paradise that I had painted in my mind.

Nine years ago, on a visit to Japan, I was reminded of the stories I had heard and family photos I had seen of Kashmir. The mountains, vast countryside, veteran trees and traditional hut homes all seemed so familiar.

excerpt from If One Uses Soft Words, Even Plain Rice Tastes Good

You were kicked out of Eden. When I read your book, I feel that loss.

How did you find your collaborators—Beth Wilkinson of Lindsay Magazine, who handled the publication’s design, and photographer Noa Nguyen?

I bought Beth’s magazine, Lindsay, and it really resonated with me. I’ve seen a lot of publications about stories from around the world, but I think this one was a bit more special. It didn’t have such a Western gaze. It respected that it was coming from a Western perspective, but it didn’t allow that perspective to supersede or overtake the stories featured. We were actually going to produce a different magazine together, but I decided that I wanted to start slowly, with a book first.

Noa, I found through Instagram. She resonated with my idea and the proverbs, as well. She really understood the art direction and philosophy behind what I was trying to do.

We started with a set of twenty proverbs and I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, this is way too hard!’ So we cut it down to about eight. With each proverb, we sat down and thought about what we wanted the picture to look like, what we wanted it to represent. We looked at themes and mood boards and tried to agree on the aesthetic and feeling.

I tried not to be too prescriptive because I actually wasn’t there, in Japan, when photography was done. The collaboration worked out well because Noa was so passionate and self-directed. So it was quite lovely.

There’s a lot of symbolism in your book.

There’s little bits of symbolism throughout the book. I tried to make, with every picture, some connection to Kashmiri culture, with food or dress.

In one of the photos, Hako is wearing a bandana which is similar to one of the scarves that my grandmother used to wear over her head. And the clogs, my grandmother wears clogs when she’s visiting the kitchen, because it’s a sacred space.

The Japanese kitchen is also similar to that of my culture. The kitchen is central. There’s a vegetable garden and farm animals on the outside. It’s very reminiscent of my own ancestors’ homes.

Now, I’m going to ask you about your day job. I think it’s important for people to know that creatives who birth really important cultural work might also take care of their day-to-day expenses with a different source of income.

Yes, outside of the fashion label and the photobook, I work as a service designer for governments and corporations, alike. If you think about any service you’ve used in the past, someone is in the background designing that client experience.

I truly believe the whole design industry is transferable. I get so frustrated when people try to box me into one area. Like they don’t see that someone can be good at two things. I see design as one thing, to be quite honest, no matter what type of design it is.

There are specializations, but they are so interconnected. And it’s nice to move between a tangible product like textile or a book and then do something conceptual like service design or photography. I like moving between mediums because I get to use all the sides of my brain.

There’s a name for people who move through the world like you, Priyanka. You’re a multipotentialite!

If One Uses Soft Words, Even Plain Rice Tastes Good was published by Oak Park Studio.

Your turn

How have you spanned disciplines in your creative or professional life? Have you used your multipotentiality to lift up or preserve your cultural heritage? Share your story in the comments.

Add to the conversation...