I had always understood multipotentialites as a certain type of person: the kind who would dare to take a tiny bite from all the flavors in an assorted box of chocolates. People whose thirst for wide knowledge led them on rich adventures into a medley of possibilities.

But when I picked up the autobiography Song In A Weary Throat by human rights activist, poet, lawyer, professor, and priest, Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray, I came to understand that some of us don’t necessarily adopt multipotentiality to expand a personal horizon. Sometimes it’s an audacious attempt to turn the whole world upside down.

“One life, two lives, three lives, more: Pauli Murray made an indelible mark on [ . . . ] history in multiple modes rarely found in one career.”

Elizabeth Alexander, poet

Pauli Murray led a kick-down barriers kinda life. Raised in the Upland South of the United States, at a time when the descendants of the enslaved were still counting the months, years, and decades since they had obtained freedom (47 years at the time of Murray’s birth). They resisted Jim Crow – the laws that kept “Coloreds” separate from “Whites” – not because they hoped to rub elbows with the privileged grandchildren of former masters, but because segregation was deadly.

Jim Crow meant that at age eight, young Pauli was nearly mobbed at a train station. Their aunt had broken her only pair of glasses and literally could not see that she had placed Pauli and their luggage inside a Whites-only waiting room. Before they could board, little Pauli found themself surrounded by a sea of blood-red faces. The law was new, as the station had not always been segregated. But the Latin-born expression “ignorance of the law excuses not” made aunt and niece vulnerable to whatever punishments met people who dared cross the color lines.

This Jim Crow horror show encouraged an adult Pauli to pick up a pen and begin a life of activism. They wrote poems and protest letters. Embarked on a fate-tempting campaign to save a sharecropper named Odell Waller from the death penalty. And fifteen years before history began to take note of these forms of resistance, they were arrested with a friend for refusing to move to the back of the bus in Virginia.

When, in their home state of North Carolina, they were denied admittance to a Master’s program in sociology, their story was picked up by the national press. The NAACP believed this media tactic tacky and turned down their request to fight in the courts.

Instead of studying sociology, Pauli moved in a different direction, and landed themself in law school at Howard University. While there, they wrote, as their thesis paper, the legal argument, that would help in the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education, which made “separate but equal” education illegal across the country.

Upon graduating, Murray thought they’d give Harvard Law School a try, hoping the prestige of an Ivy League would help them become more competitive in the job market. Their male colleagues at Howard laughed at the thought. Didn’t they know that Harvard accepted “Negroes” but did not admit women? They applied anyway, with a recommendation letter from the sitting president of the United States, Franklin D. Roosevelt – a Harvard man himself. Pauli had become good friends with his wife Eleanor!

Harvard declined. In 1944, the institution did not invite women to matriculate. Pauli appealed this decision, stating in their correspondence “Gentlemen, I would gladly change my sex to meet your requirements but since the way to such change has not been revealed to me, I have no recourse but to appeal to you to change your minds…”

“What they call you is one thing. What you answer to is something else.”

Lucille Clifton, poet

In their autobiography, Pauli publicly positioned themself as woman. Much of their advocacy work was in service of smashing the patriarchy and encouraging equal opportunities regardless of gender. They were a founding member of the National Organization for Women, along with author/activist Betty Friedan. Ruth Bader Ginsburg credited Pauli’s legal theories with influencing arguments in the US Supreme Court Case Reed v. Reed, which ended legal “sex” discrimination in the nation.

However, in early private letters to family, Pauli described their personality as “he/she”. They saw themself as an in-between in almost all of their identities. As mixed-race, in-between Black and White, even though the culture regarded them only as African American. They hated the label “Black” and did not feel it fully encapsulated their diverse ancestry.

By the 1930s, they sought medical examinations and treatments to affirm their male sense of self. Examinations were conducted by physicians, but hormone treatment denied.

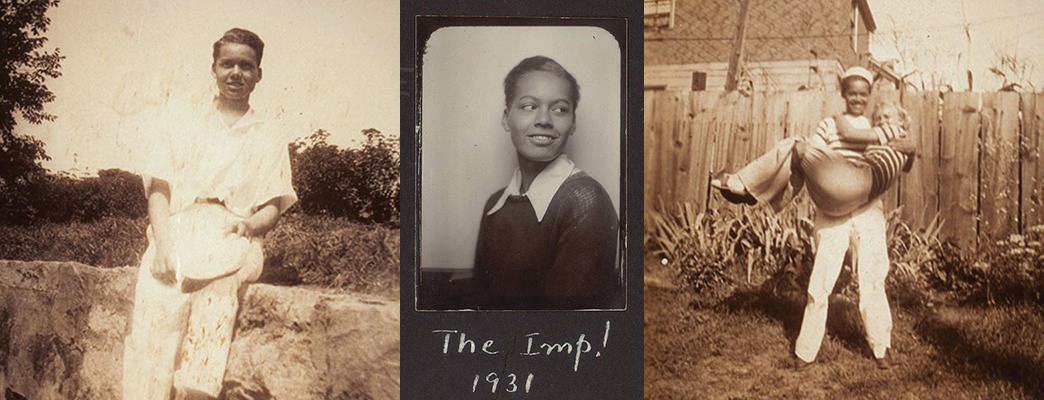

On road trips, they took advantage of anonymity to dress in uniforms designated for men. They documented their masculine presentations in a photo album and captioned their looks as “The Dude,” “Mike and Ike,” and “The Vagabond”.

The McCarthy era in America saw them cut off from a job opportunity with Cornell University. The US State Department and the university conducted a background check and found that Pauli had revealed to their physician they believed they were homosexual. This admission, in the early 1950’s, was considered un-American.

Murray responded to this latest, in a long list of societal exclusions, by writing an entire memoir, Proud Shoes, detailing their maternal family’s history and contributions in weaving (growing and harvesting) the fabric that made America.

Traditionally, we celebrate Black History Month with a spirit of reverence, often only acknowledging the mountaintop experiences of people we regard as s/heroes. However, I feel it best honors our truths to also discuss those valley experiences. As Pauli testifies in a poetic verse from their chapbook Dark Testament, “hope is a song in a weary throat.”

Pauli Murray went to battle for people of color, women, elders, and what they coded as “other minorities” when referencing LGBTQ+ communities in the courtroom, in the pulpit, and on the page. These multi-generational, multifaceted, and intersectional skirmishes left deep scars on their psyche and well-being.

On several occasions, Murray was hospitalized with mental anguish, malnourishment, and other serious health concerns. They were often in need of surgeries that had to be postponed for painfully long periods due to lack of insurance or access to funds.

They earned accolades, honors, and prestigious degrees, but rarely earned a living wage for their work.

As we amplify the legacies of African Americans in history, my hope is that we consider the ways in which the struggle for a more equitable society persists. And that we all find ways to lend our strengths (which, since we’re multipods, are numerous) to that very effort.

Your Turn

I’d love to learn how you’re lending your multipotentialite genius to fights (and restful periods) for greater equalities. What are some organizations whose causes we should champion today? And what forms of self-care do you engage while participating in the many struggles toward freedom?

I love this piece so much. I can relate to some of these parts about the “in between” identity as a white Mexican woman who feels a strong affinity for Mexicana and Latina struggles. Yet I show up in a white body, so there’s a certain amount of sheepishness about my privilege and my ability to “choose identities” depending on the company around me. I am grateful to learn about the story of Pauli Murray. My impression is that this multi-pod community is important to so many of us because we are accepted as we are, not “misfits” but rather multi-dimensional and full of rich contributions. Thank you.

Yes! I’m so happy the article resonates with you. And it’s wonderful to have a community where all of our in-betweenness is celebrated.

Thank your for this story. Having to answer the question (or just see it in their eyes) of “But where are you from?” is one way I have carried the burden my whole life. Lately I try to put it down but now feel like I have to keep on or people will not know I really am the daughter of a green card carrying mother and my melanin comes from Native American and Mexican heritage. Something to be proud of but it also becomes heavy at times. I recommend buildingmovement.org as a place where people in the non-profit world can go to find resources, tools and even processes for engaging in social change.

Thank you for recommending Building Movement! A non-profit that supports non-profits, very cool!!

Dear Malika, thanks so much for writing about Pauli Murray. It is wonderful to be introduced to multipotentialite heroes that we would never hear about otherwise. I will look for their autobiography – which is one of my favourite forms. As for my activism – it has been sporadic. I refer to myself as a manysoul, which psychiatrists refer to as dissociative identity disorder. I have been in-between all my life, but especially when I became ill in my twenties and experienced a lot of medical gaslighting. My voice has been silent for a while now – health issues, and more recently a warning to shut up in my writing after my Mum’s death. Recovering from her death has made me more determined to speak again, although it is challenging with so many health issues. So my answer, I guess, is I just do the best I can, and one day I hope my writing will speak for me and others like me. Apologies if you respond and I don’t reply – I don’t get notifications that you have – perhaps the tech gurus there can fix that. <3

Yes, Jane, to “I just do the best I can” which is more than enough!

Great piece! Thanks for sharing their story. This is only one reason why I love Black History Month because we get to learn about the unspoken s/heroes!

Yes! It’s a reclamation. A necessary time to challenge all the erasures. Thank you for reading!!

Thank you very much for this article. There is definitly a lack of non-binary rolemodels… My teenager discovered early to be an “in-between-person”, so it is very important to have examples!

Last week I watched “Amend, The Fight For America” on Netflix. In episode 4 there are lots of informations about Pauli Murray and now I read again about her. There are no coincidences in the world 😉